MSCHF Doesn’t Just Make Video Games, It Is One

The art collective acting like one big open world game.

The botched CrowdStrike update from July 2024 was a shock in many ways. ATMs crashed, flights were grounded and IT systems everywhere ground to a halt. But in the halls of MSCHF, something else was happening. In fact, despite the shock of CrowdStrike for most, the outage had a delightfully unexpected effect on MSCHF’s game, Tontine. “We think that CrowdStrike might’ve nuked some of the bots that were playing Tontine,” said Kevin Wiesner, Co-Chief Creative Officer of MSCHF. Tontine is a lo-fi graphic styled game created by MSCHF based on an investment scheme dating back to the 1600s. Effectively, it’s a contract between a group of people who all invest an equal amount of money and split the dividends annually, except the only person that can claim it is the last remaining person alive. Despite Tontine technically being illegal today, MSCHF brought it into the 21st century with a $10 entry fee and an obligatory rule that every member must log in once a day and hit the “I am still alive” button. Miss one and it’s game over.

Naturally, this kind of game would attract cheaters. “We like leaving large parts of the project essentially incomplete until people start interacting with 'em - like with Tontine. We knew people were going to use bots, we just had no idea that CrowdStrike would nuke half of them,” said Wiesner. Now there’s only 226 players remaining and a similar unexpected glitch could shift the stakes at any time. “This was a narrative we didn’t see coming.” This unexpected development for Tontine is what makes MSCHF so different to a lifestyle brand that spits out passive products. MSCHF’s projects are more like open world games with a plethora of side quests and secret easter eggs. Better yet, those that engage in MSCHF’s great open world simulation act like hackers or modders, bending the game to the way they want to play it. “Our kind of philosophy is there's no such thing as cheating. We love seeing what people do, everything is fair game, the crazier the better,” says Wiesner.

It’s understandable that those that play MSCHF’s games would want to cheat - there’s usually some pretty hefty prizes on the line. For Tontine, it’s a smooth $71,400 USD. For MSCHF’s Box back in 2020, it could’ve been a Rolex, a Vespa Scooter, or - if you were really lucky - a chewed piece of gum. MSCHF’s Box emerged during the height of the loot box controversy in video games. Massive publishers like Epic Games were being scrutinised for their gambling-esque products called “loot boxes” where players (typically children) would pay real money to buy a mystery box of in-game items that could potentially enhance gameplay. Amongst the whirlwind of class action lawsuits, MSCHF, as ever, created the timely MSCHF Box. “A lot of the games that we make interface with the real world as much as possible.” says Lukas Bentel, Co-Chief Creative Officer of MSCHF. Players could buy a limited range of mystery boxes which, much like loot boxes, could be filled with high value items like an LV Bag or a Nintendo Switch. Or it could be a tube of toothpaste. Players were given the option to open the box and redeem the items within it (valued between $0-7K) OR they could wait 100 days and sell it back to MSCHF for $1000. Naturally, the theatre of a surprise unboxing was catnip for influencers, with streamers like ConnorTv and ItsYeBoi breaking the 100 day contract in front of their millions of subscribers. The brilliance of such a simple yet psychologically stimulating idea like MSCHF Box lay in its ability to show the players all the cards, yet still prompt many different outcomes.

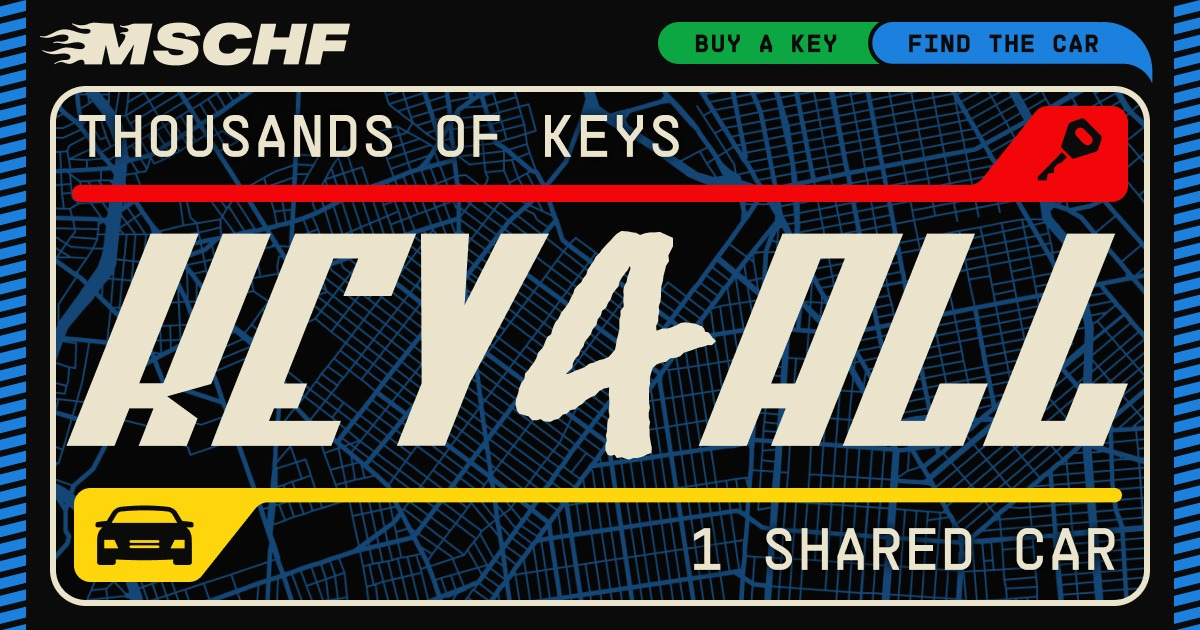

Key4All was another MSCHF game with endless outcomes. It took the ingredients of the share car economy and Grand Theft Auto and mashed them into one unscripted live action saga. “We have rebuilt the entirety of ZipCar with a fleet of one single vehicle, but rather than a study in shared resource management, Key4All has been engineered to be Grand Theft Auto: Tragedy Of The Commons,” said MSCHF in the Key4All manifesto. The game was simple. After purchasing a key, everyone had access to a car, starting in New York City. The catch was, no one knew where it was. To find the car, drivers could call MSCHF’s car location hotline which offered hints at its whereabouts. If you found the car, it was yours. But if you wanted to drive, then you had to accept the risk of taking the car out in the world where another key holder may snatch the vehicle out from under you. The car made its way around the East Coast with people slapping their stickers, stamps and doodles on the interiors. Like some sort of toilet cubicle on wheels. People even left gifts for each other. From weed to sauce condiments to art works. This was akin to game coders in the 80’s leaving easter egg’s inside games like Adventure as an “XX was here” for players to discover. According to the r/Key4All subreddit, the car made its way all over the country, from Philadelphia to Arizona, finally landing at MSCHF’s Art2 exhibition in LA. The end result felt like a collaborative art piece between every Key4All driver, documenting a renegade road trip across the country.

Of course, MSCHF have also made actual video games with the likes of BTS In Battle, Dino Swords and Chair Simulator to name a few. But it feels like the entire discography of MSCHF’s projects play out like one big open world video game, with the best leveraging the mechanics of modern game design. Whether they’re prodding the pain points of addictive loot boxes in MSCHF Box or personifying the experience of carjacking in GTA through MSCHF Key4All, they invert video game fantasies into real life escapades. Bentel puts it best himself. “I think a lot of MSCHF’s game type things all loosely tread that cute little line of" when you die in the game, you die in real life.”